Starting at about eight in the morning, snow came down in a hurry. It was cold out, probably in the upper twenties, and the snow was sticking. By afternoon, after I had shoveled the driveway, I was wondering if it were possible to hit practice balls without losing most of them in the snow, which was about three inches deep. The prospect of hitting balls over the snow quickly won out over the propect of losing most of them until the snow melted, and I threw down my practice mat on the front walkway. The obvious choice was to use my Callaway practice balls, since they are orange and might be easier to find, once I hit them.

Starting at about eight in the morning, snow came down in a hurry. It was cold out, probably in the upper twenties, and the snow was sticking. By afternoon, after I had shoveled the driveway, I was wondering if it were possible to hit practice balls without losing most of them in the snow, which was about three inches deep. The prospect of hitting balls over the snow quickly won out over the propect of losing most of them until the snow melted, and I threw down my practice mat on the front walkway. The obvious choice was to use my Callaway practice balls, since they are orange and might be easier to find, once I hit them.So I set up and started hitting balls with the left arm alone drill. Out of the first dozen or so, I yanked several over the stone wall that marks the left boundary of my property (I found all of them later), but it didn't take long to get warmed up and get in a groove where I could hit almost every ball straight ahead and with a good, clean hit. With this encouragement, I collected the balls, finding all of them in the snow, and decided to try hitting with a full swing.

Hitting thirty balls was all the encouragement I needed. I found that I was hitting the balls out towards my target and almost every swing was a clean hit. When I finished, I thought, maybe I should film my swing at this point, as a kind of reality check, and see what it looks like. Amazingly, I found all the balls in the snow again and set up some on the mat to hit in front of the camcorder.

In the video below, you'll see that I'm wearing my Sorrels, the boots I typically wear when I know I'm going to be walking around the backyard in bad conditions looking for the practice balls that I've hit. You'll also notice that I'm dressed pretty lightly. That's because I know I'm going to be outside hitting balls only for a few minutes, just long enough to get a little video footage.

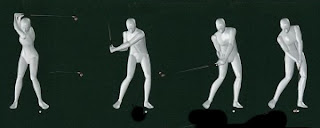

In the video, I've added some lines to highlight my swing plane and the club position at various points in the swing. You'll also hear my stamping my feet to get some snow off my Sorrels before I start hitting with the camcorder behind me. In all these shots, I'm using my typical practice club, my seven-iron.

As you can see, I've got a reasonably rhythmical swing on a fairly good plane and with a good follow-through, very different from what it was a few months ago. If I can do it with my video software, I'll try to do a side-by-side video soon that shows my swing as it was not too long ago compared to what it looks like now. The improvement that you'll see is the result of daily practice and almost daily videotaping and review. Then, of course, there's the left arm alone drill. It is just fantastic!

In the slo-mo section (from behind) of the video, you can see some good aspects of the swing and several that need some work and readjustment. For example, on the backswing, the plane is a little too flat. In an earlier video, the plane was more vertical and on plane throughout the swing. Now it's dropped a bit, and I want to fix that. I added some graphics to highlight the target line and other lines in the swing that I like to pay attention to. Another problem that I see is at the top of the swing, where I go past parallel to the target line and past parallel to the ground. On the plus side, the downswing looks pretty good -- on plane again and maintaining the spine angle and a right angle between the swing plane and the spine angle. And the end of the follow-through is almost parallel to the original swing plane, and my balance is good, most of my weight on my left heel.

Now on New Year's Day, I'll go out with the Callaways again and work on the plane of the backswing. I also want to get over my excitement at how good the swing feels and pay closer attention to staying in the shot longer and really delaying the release, getting over my eagerness to hit another great shot and work on a smooth, unhurried approach to the ball.

As I was finishing this practice session, with good results, I might add, I remembered videos I had seen of Moe Norman, the great Canadian pro, who famously swung on a single plane and reputedly always hit the ball straight. Not bad company, I thought. I went to sleep that night thinking that I had made another step higher up the ladder toward the ideal swing. After a good night’s sleep, morning clarified that thought. Waking up to reality in the next post.

As I was finishing this practice session, with good results, I might add, I remembered videos I had seen of Moe Norman, the great Canadian pro, who famously swung on a single plane and reputedly always hit the ball straight. Not bad company, I thought. I went to sleep that night thinking that I had made another step higher up the ladder toward the ideal swing. After a good night’s sleep, morning clarified that thought. Waking up to reality in the next post.